Nutrition Freebies for Adults

(These weight loss tools and nutrition freebies are not recommended for those with eating disorders, children/teens, people on a prescribed medical nutrition therapy, underweight persons, and pregnant or lactating women. It is a good idea to consult with a dietitian who is familiar with your medical history before starting a new dietary plan.)

Want the best fast food options?

✅ Find out the answers to these questions plus so much MORE:

☕ What are the best McCafe drinks?

🍕 What are the best items at Little Caesars?

🍗 What are the healthy options at Bojangles?

Note: Unfortunately, it's not possible to get what I would call a health-promoting and balanced meal at some restaurants. In those cases, I get a small snack (if I'm hungry) and have a meal later at another place with better options.

The general recommendation for weight loss for women is 1,200-1,500 calories per day. For men, it is 1,500-1,800 calories per day. I do not recommend going below these levels without close medical supervision. The NIH Body Weight Planner is a great tool to calculate realistic calorie goals for weight loss.

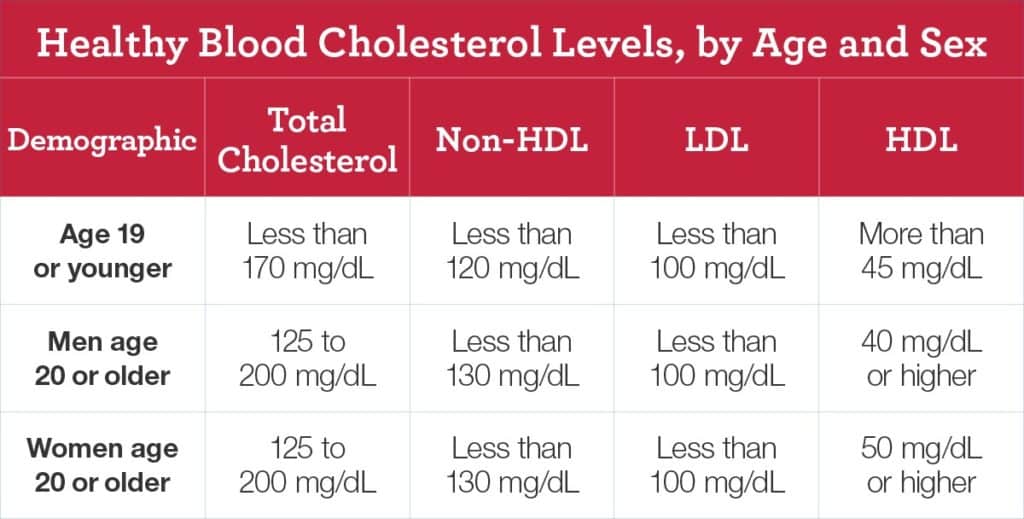

Cholesterol Levels By Age Chart

The blood cholesterol levels that are considered optimal vary by age and sex. The goal is to achieve a lower LDL cholesterol (the “bad” cholesterol) and a higher HDL cholesterol (the “good” cholesterol). The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has a helpful chart that shows desired targets (source):

Total cholesterol equals HDL + LDL + 20% triglycerides (though using the Martin-Hopkins equation to calculate LDL throws this calculation off a bit). Non-HDL = Total cholesterol – HDL OR VLDL + LDL.

If you have diabetes or CHD, your LDL target is <70 mg/dL, and your non-HDL goal may be lowered to <100 mg/dL. Though not included in the chart above, target triglycerides for adults are typically <150 mg/dL. Got it?

Factors like age, genetics, family history, and race can all impact cholesterol levels. Another factor that can affect blood cholesterol is your diet.

Dietary cholesterol is only present in animal-derived foods. However, the most recent evidence indicates that dietary cholesterol does not play as large a role in raising our blood cholesterol as we once thought.

Saturated fat raises cholesterol (particularly LDL), so saturated fat consumption to under 10% of calories is advised. Additionally, replacing saturated fats in the diet with unsaturated fats is encouraged. Replacing saturated fat with carbohydrates may not reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Deficiencies from Food Group Elimination

Dietitians usually recommend a "foods first" approach, i.e., getting nutrients from foods rather than supplements. When this isn't possible, a supplement may be warranted.

Water-soluble vitamins are of particular concern since it can only take a few weeks for a severe deficiency to develop without intake. ("Water-soluble vitamins" means the B vitamins and vitamin C.)

If you're on a special diet that cut out a food group, this nutrition freebie will help you learn which nutrient deficiencies you may be at risk for. It also discusses alternate ways to cover the B vitamins if you don't eat grains:

Please keep in mind that many micronutrients (even the water-soluble ones) have a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL). The UL is the highest level of daily intake that is unlikely to result in adverse effects.

Don't just take high-dose supplements if you suspect you're at risk of nutrient deficiency! Consult with your physician or dietitian to help you figure out the next steps.

Healthy Living Freebies for Parents

- CDC Child and Teen BMI Calculator

- FREE MyPlate Activities for Kids

- FREE MyPlate Information for Teens